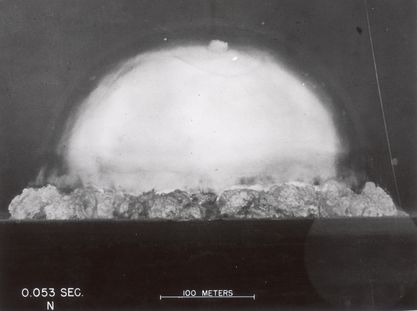

On a chilly summer morning, at a secluded Air Force base in Alamogordo, New Mexico, J. Robert Oppenheimer braced himself upon a stake in the ground, his eyes fixed on the northern horizon. It was 5:29 and Oppenheimer stood anxiously awaiting the culmination of the Manhattan Project’s efforts, a monumental test he had dubbed Trinity. He had covertly directed the project with a small army of scientists over the previous three years, designing the coup de grace to World War II with implications that even he could not yet really fathom. Clutching the stake and crouching forward, toward the direction of the imminent blast, Oppenheimer did not really know what to expect, but he knew he was about to witness something that would now be beyond his control.1

At that point, the explosion of a plutonium bomb with Trinity was the most prodigious test ever performed by mankind, and with its success a new era began that, through the next 60 years, would see over two thousand more nuclear tests performed throughout the world.2 Beyond the sheer number of nuclear tests performed, one can view the entire Atomic Age, from 1945 to the present, as a test, a trial of mankind’s ability to endure the weight, responsibility, and consequences that come with the possession of atomic knowledge. The successful development of an atomic bomb by the United States was a watershed moment in the history of the human race, and possession of the bomb would test the United States’, and the international community’s capacity to handle such power responsibly.

Exactly three weeks after the successful Trinity blast, the people of Hiroshima, Japan became the first casualties of an atomic bomb. Though many scientists had wanted a demonstration of the bomb on a neutral, uninhabited area, US leaders instead opted to use the bustling city of Hiroshima as their stage (they knew the city housed a significant Japanese military presence, but those soldiers only accounted for roughly 10% of the 70,000 instantly killed). Secretary of War Henry Stimson was one of those in favor of a demonstration, giving the Japanese more credit than others in the government and the army who considered the Japanese leadership irrational, fanatical, and unlikely to be swayed by any exhibition of the bomb. The decision to bomb Hiroshima without a demonstration relied on the assumption that the Japanese would not be impressed enough to lay down their arms and the US would still be forced to make a hard-fought and costly incursion. On top of this, there was the potential that the bomb would not detonate during the demonstration, which would waste limited resources and be an embarrassment to the United States. As Richard Rhodes explains,

“The point of warning the Japanese was to encourage an early surrender in the hope of avoiding a bloody invasion; the trouble with waiting until the Soviet Union entered the war was that it left Truman where he had dangled uncomfortably for months: over Stalin’s barrel, dependent on the USSR for military intervention in Manchuria to tie up the Japanese armies there.”3

Because of concerns for the USSR’s entrance into the Pacific Theatre, which would give them solid footing in establishing power in Asia, the notion that America had any obligation to demonstrate the atomic bomb’s power became foolish and contradictory to the interests of the nation. Truman instead offered an ominous warning from the Potsdam Conference, telling “the government of Japan to proclaim… the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces… The alternative [being] prompt and utter destruction.”4 Unfortunately, the Japanese were skeptical of Truman’s bold words and, refusing to accept the conditions set forth in the Potsdam Declaration, continued to fight a futile battle. “Unconditional surrender seemed to the Japanese leadership a demand to give up its essential and historic polity, a demand that under similar circumstances Americans also might hesitate to meet even at the price of their lives.”5

It is understandable why President Truman and the United States did not feel compelled to give Japan a more sufficient warning before bombing Hiroshima. After all, it had been less than four years since Japan’s sneaky attack on Pearl Harbor, a dramatic bombing in its own right that had taken the lives of more than 2,000 US troops, had drawn a reluctant country into World War II, and for which no warning or signal had been given. However, as justified as one may argue America was, by not allowing a test to take place and demonstrating the new atomic weapon prior to Hiroshima, the United States set a precedent for secrecy that would precipitate the beginning of the Cold War. The American leadership’s mishandling of such a privileged position was humanity’s first failure in the Atomic Age.

Nowhere is the notion of “testing” as a metaphor for the Atomic Age more apparent and palpable than in the United States’ activities in the Marshall Islands. Beginning in 1946, the Marshall Islands and surrounding atolls became the United States’ laboratory for testing of nuclear weapons. Pacific Proving Grounds was the title America gave to the area and the ensuing experiments that took place, but as one of the natives contaminated with radioactive fallout revealed, the main thing America proved was that “they are smart at doing stupid things.”6 From 1946 to 1962, the United States tested 70 nuclear weapons at Pacific Proving Grounds, beginning with the first series named Operation Crossroads. The second series, Operation Castle, had the highest total yield of any series of nuclear tests ever performed.7

The most significant of the nuclear tests performed during Operation Castle came on March 1, 1954, with the Bravo blast. A 15-megaton hydrogen bomb, Castle-Bravo produced the largest nuclear explosion ever carried out by the United States.8 Immediately, and in the days after the blast, radioactive fallout directly contaminated more than 250 people, a fact the US Army insisted was unintentional. It was claimed that an unanticipated change in wind direction was to blame for the fallout from Bravo spreading over inhabited islands, including Rongelap. The ensuing radioactive fallout also contaminated Army weathermen stationed in the Marshall Islands working for the United States during the test; they refused to believe the Army’s insistence that the wind change was not anticipated. What is more troubling is their opinion that the contamination was not simply a careless accident but a preconceived plan by the US military in an attempt to gather information on the effects that radioactive fallout has on human beings.

There is considerable evidence that the American officers were well aware, if not anticipating, the potential for human contamination following Castle-Bravo. The first thing to be considered is the total lack of precautions taken by the United States. During the initial Trinity test, servicemen were on standby to evacuate the entire state of New Mexico, if necessary, an area larger than the distance between Castle-Bravo and the Marshall Islands. The day before the detonation, the USS Gypsy passed right by the inhabited island of Rongelap, never offering to pick up any of the natives nor offering any forewarning of the impending explosion. 9 What seems to further implicate the United States is the manner in which it acted after the blast. When it became clear that the radioactive plume from Castle-Bravo had carried through the atolls and traveled over Rongelap, the Navy conducted a swift evacuation, beginning treatment of the contaminated people and a study called project 4.1, the “Study of Response of Human Beings Accidentally Exposed to Significant Fallout Radiation.”10 While an accidental contamination would logically lead to prompt treatment, the contaminated Marshallese expressed that the American personnel seemed more interested in inspecting and observing their symptoms than acting in any way to help them. 11

The effects of radiation on the contaminated Marshallese were dire. The people began to see physical and mental abnormalities that they had never known in the past. Children born with disproportionately large heads, a rampant number of miscarriages, and strange cancers began to plague the people. The most macabre of the results attributed to nuclear fallout came from a woman who described a child she had soon after Operation Castle had ceased. She described her newborn as something resembling “the innards of a beast.” The torment she suffered because of this and multiple stillbirths afterwards was all due to what was simply known to them as “the poison.” 12

After the contamination of the Marshallese and a growing negative atmosphere that came to cloud the Pacific Proving Ground, America’s testing of nuclear weapons finally ceased there in 1962. With the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty a year later, the United States and the Soviet Union began to make progress towards curbing the environmental effects that the weapons were causing. Though the ban would still permit nuclear testing underground, the ban forbade any further testing above ground, underwater, or in outer space.

While scientists like Oppenheimer possessed significant influence during the Manhattan Project, in the process of actually developing an atomic bomb, once they had completed that task, their stature quickly diminished. The American military had counted on scientists to help deliver an expedient finish to World War II, but once the scientists came through, their views on how the weapons should be used were all but ignored.

The Atomic Energy Commission, founded at the end of WWII and chaired by Oppenheimer, recommended against any development of the more powerful ‘super’ hydrogen bomb, which had been conceived at Los Alamos by physicist Edward Teller. Oppenheimer’s stated opinion was, “In determining not to proceed to develop the super bomb, we see a unique opportunity of providing by example some limitations on the totality of war and thus limiting the fear and arousing the hopes of mankind.”13

Though Oppenheimer believed that the atomic bomb was necessary in thwarting further expansion into Europe by the USSR, he didn’t see the rationale in creating even more powerful weapons. The fact that the United States would be precipitating the advancement of weapons of mass destruction was one thing, but more significantly, Oppenheimer believed the atomic bomb could still function as an effective military weapon to be used in good conscience, but the capacity of the hydrogen bomb was too extreme and any decision to use it in the future would certainly involve the killing of many innocent civilians. He felt that the United States should not proceed to create this super bomb simply to intimidate the USSR. It was Oppenheimer’s opinion that “by producing more A-bombs, refining their design to include tactical uses, and having a better delivery capability… the United States would be able to keep its military superiority over the USSR for the indefinite future.”14

He was an American hero at the time, the “father of the atomic bomb”, but Oppenheimer’s voice was ignored. The role of scientist as a peaceful moderator was not as well received as the role of weapon manufacturer. With the Soviet detonation of their atomic bomb in 1949, and fear being stirred up by the arrest of Klaus Fuchs soon after, Truman ordered the go ahead for the American development of a hydrogen bomb.15 Anxiety and paranoia had influenced another critical decision by the United States, and the opportunity to take a more responsible, openhanded stance once again slipped away.

The Atomic Age thus far can be seen as a test, a test of mankind’s capacity for discretion and its ability to handle an imposing, elemental-power once solely reserved for the heavens. Though many consider the end of the Atomic Age as having occurred with the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, that is simply not the case. It is true that times have changed, that an insecure era concerned with Soviet-spies, bomb-shelters, and radioactive-monsters has passed, but the devastating weapon that spawned all these fears can still be found lurking in arms caches around the world. The Atomic Age carries on to this very moment and mankind is in perhaps a more perilous position than it was even in those tense October days during the Cuban Missile Crisis. With the rise of terrorism, the growing influence of religious fundamentalist-fanatics, and with thousands of nuclear weapons unaccounted for, the threats posed to humanity during the Atomic Age are as palpable as ever. One need not look any further than the events of September 11, 2001 to see the uncertain situation in which humanity still remains. The advancement of diplomacy and international cooperation are realities for sure, but the test of whether or not the human race will survive the Atomic Age remains to be seen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.